The Moscow Jewish Theater: A Translation from Joseph Roth (1894 - 1939)

On the eve of a partisan U.S. election, we must remember the vitality of the human spirit when unleashed from hate. Zachary’s translation of writer, Joseph Roth, inspires us.

Translation of Joseph Roth by Zachary Suri

Joseph Roth was one of the great Jewish writers of the 20th century, but he hardly ever wrote about his Judaism. Born in present-day Ukraine to a traditional religious family, Roth became a literary sensation in Vienna and Berlin, writing feuilletons (literary articles) in the great German-speaking newspapers of the day. For the most part, Roth adopts a distinctly German perspective, even when reporting on Jewish refugees or the devastation of the First World War. His distinctly Jewish literary style peeks through only in some of his lesser-known novels and in his travel accounts of Eastern Europe. In 1926, Roth, long sympathetic to socialism, visited the Soviet Union for the Frankfurter Zeitung, a leading Frankfurt newspaper. He produced more than two dozen articles celebrating the industriousness of the USSR, but mocking its didactic culture mercilessly. In “The Moscow Jewish Theater” (Das Moskauer Jüdische Theater) published in 1928 by the avant-garde Berlin press, Verlag Die Schmiede, Roth reveals the depth of his emotional, artistic, and political connection to Judaism. The essay was published in a small volume alongside reflections from two other German-Jewish left-wing writers on the Moscow State Jewish Theater, a center of Yiddish literary and artistic creativity.

This translation was prepared based on research conducted this summer at the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek in Leipzig and the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin generously sponsored by the Jehiel R. Elyachar Foundation Travel Fellowship in Judaic Studies. Thanks to Prof. Austen Hinkley for his assistance with this translation - ZS.

Fifteen years have gone by since I saw a Yiddish theater for the first time. It arrived in Leopoldstadt1 from Vilna. I still remember the posters clearly. They differed from the advertisements of the other theaters by virtue of a certain simplicity, a quasi-provisional crudeness, a primitive coarseness. They were not routine playbills; they were probably made with a hand pressfrom a cheap and tactless yellow, without borders, randomly pasted onto walls and not on the official billboards. Fixed in nooks that smelled rank, they stood out and were much more effective than more refined posters. They were composed in a language one can often hear spoken by Jews in the small coffeehouses of the district, but which seemed to exist only as sound, never as a written image. On these posters the Yiddish was written with Latin letters. It was like a grotesque German. It was coarse and tender at the same time. Many words were German and had Slavic diminutive endings. Spelled slowly, they sounded preposterous. Spoken quickly, they sounded tender.

In the evening, on the stage, they were spoken quickly. They played an operetta. One of those operettas from the infancy of the Yiddish theater, which used to be called “Tragic Dramas with Song and Dance.” I have never found this phrase laughable. It never seemed to me to contain a contradiction. I did not, for instance, have to think about ancient tragedy. It was enough to think about Jewish daily life, which is a kind of tragic drama with song and dance. These operettas, of which I saw many, were kitschy, sentimental, and yet true. Their problems—because these operettas contained problems—were clumsy, their plots haphazard. Their characters were superficially typical. Their situations only seemed to be there because of the songs that they characterized. But these songs actually made up the artistic meaning of the Yiddish theater. Because of these songs (mostly folk songs, oriental and Slavic melodies, declaimed by untrained voices, but sung more with the heart than with the throat, at the end repeated by everyone), because of these songs the Yiddish theater was exonerated. Their ballad-like lyrics gathered together the proceedings that had just played out so awkwardly and amateurishly. The melody rang behind, not beside, the content. The words and the events lay in it. Thus, one saw deep behind them the great destiny of which they were a small part. Thus, there extended beneath them—vast, dense, and misty—a world which one knew to be the tragic drama that the song and the dance had only sent in front of the scenery and had not yet revealed itself. What stood behind the primitive Yiddish stage was high, tragic art and the exoneration of the stage.

Years later, I saw traveling Yiddish troupes three or four more times in various cities of the West. I lamented the European development which threatened to take over the Yiddish theater. I lamented that it fell victim to the strict European division of so-called dramatic categories. That it had the ambition to produce “pure tragedies” and that it was determined to take part in the Western theater—without Western traditions. That one could play Sholom Asch on German stages almost without change and without concession, seemed to me evidence of the decline of the Yiddish theater and not of its ascent, as was proclaimed. I have never ceased to maintain that Sholom Asch is a Yiddish brother of Sudermann. That a Western civilized, flattened, diluted layer of emigrant Jews saw their European ambitions assuaged with the sight of a “modern” Jewish play, structured according to Western dramaturgical rules, seemed to be just as silly as the childish delight of naive Zionists at the good shots of Palestinian gunmen and all the well-fortified mischief that is called the “Rebirth of the Jewish Nation.”

I did not understand this ambition which called itself national but was only a civilizational ambition. Why not “Tragic Drama with Song and Dance”? Why not crude, yellow playbills made with a hand press—poor, but striking? Why not an unpunctual start? Why not a cloak room and infants in the hall? Why not an incessantly long intermission? Why suddenly this respectable European reliability, this closing time, this prohibition on wearing a hat in the hall, smoking, and eating oranges?

Only on one other occasion—in Paris—have I seen such an Eastern, unregulated theater, in the Jewish quarter. There were only a few performances. It was a poor traveling theater. There they sang the songs that I had heard fifteen years ago in Leopoldstadt. They played tragic dramas with song and dance. The audience interrupted the actors in the middle of their lines. An actor emerged, pushed the agitators to the side and gave a little address, then the play went on. The seats were not numbered. Baby carriages stood in the cloakroom. Infants wept in the auditorium.

A few weeks later the “Habima” came to Paris. I have never seen this Hebrew theater. If, of fourteen million Jews, barely three million understand Hebrew, and these three of the fourteen millions scattered across the whole world are likewise scattered, I cannot understand the existence of a Hebrew theater. Many experts were delighted by the “Habima.” I understand that one is delighted by a luxury item. It can have performative worth. But only the necessary is artistic.

In the winter of 1926, I visited the Yiddish Theater in Moscow. After the first act, Herr Granowsky invited me to tea (the intermissions in the Russian theaters are fortunately long enough to drink a cup of tea). I was incapable then of formulating an impression. Had custom permitted me to be candid and not commanded me to produce compliments, I would have spoken the following:

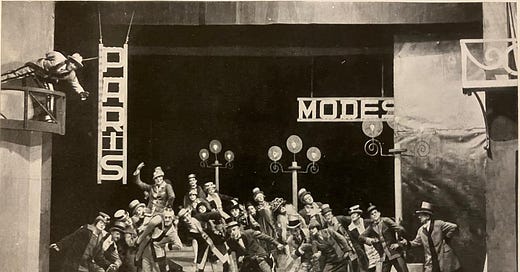

I am shaken and shocked. The garish luster of the colors left me dazzled, the noise—stunned, the liveliness of movement—confused. This theater is no longer a heightened world; it is another world. These actors are no longer bearers of roles, but enchanted bearers of a hex. They speak with voices the likes of which I have not heard in any theater in the world. They sing with the fervor of despair. When they dance, they remind me of Bacchants, as well as Hassidim. Their dialogues are like the prayers of the Jews in Tallit on Yom Kippur and like the loud profanities of the Korach mob. Their movements are like a ritual and like a mania. The scenes are not contrived or painted, but dreamed. I need an entire evening to accustom my ears to this loudness, to let my eyes feel at home in this glare. I cannot yet distinguish between intentional exaggeration and natural (or supernatural) ecstasy. Every benchmark that I bring with me from the West breaks down in this theater. This pleases me, but it helps me naught.

I needed time to accustom myself to the Yiddish theater, to its excitement, which tolerated no enhancement, which was immediately there from the first word of the first entrance on until the last word of the play. Yes, which was already there in the vestibule, in its pictures, on the stairs and on the walls. It seemed to me as if the Judaism which was depicted here were more oriental than any that one encountered elsewhere—a warmer, older Judaism, from other climes. Every notion that one might bring with into this theater of the proverbial vivaciousness of Jewish people, for instance, was exceeded by the fervid gestures of the actors. They were Jews of a higher temperature, more Jewish Jews. Their passion was of a degree more passionate. Their dejection itself obtained the face of ferocity. Their sadness was fanatical, their joy a delirium. They were a Dionysian kind of Jews.

From the moment I determined this and tried to move myself into the higher climate of the theater, I began to enjoy the performances with criticism.

It seemed to me that in the Moscow Yiddish Theater, that world appeared which I had sensed behind the stage fifteen years earlier in Leopoldstadt at the viewing of a tragic drama with song and dance. It seemed to me that the old operettas had finally received their raison d’etre and the vindication of their existence no longer had to be derived from their songs. They were “reworked.” The old songs had received new lyrics (by the way, not all new lyrics are better than the old ones). The tragedy and the comedy were refreshed—and perhaps it did not lie at all in the intention of the innovator and adjustor to make the Yiddish stage play “more authentic” and, from the pretexts for dramatics which they had been, make them into the aim of the dramatics itself. No, I have the impression, that the transformation of contingencies into the predestined happened unconsciously, and that it was the doing of a new Jewish generation, realized by a few of their representatives (Granowsky, the painter Altmann, and the extraordinary actor Michoels). I deliberately refrain from connecting this Jewish generation with the Russian Revolution to explain this somewhat. But it stands for me beyond all doubt that, without the great Russian Revolution, the Moscow Yiddish Theater would be impossible.

This theater has altered the traditions of the old Yiddish stage so skillfully that it almost looks like a protest against tradition. But it may go no further.

Eventually every innovation in art looks like a protest against tradition and is, on the contrary, its continuation. But the Moscow Yiddish Theater sometimes oversteps the law that permits the descendents to be an opposition, but not to oppose. There, where the Yiddish Theater consciously crosses from a contrived protest into a rhetorical one, its liberty begins to degenerate into that attitude which is justifiably called “chutzpah.”

I could register this chutzpah. I tried to explain it. It is certainly attributed to the influence of the revolutionary by-product, which I would like to call the “infantile sacking of the Temple.” It is that expression of a naive and insecure rationalism, which instead of silently repudiating profanes raucously. It has accompanied every revolution, and it debases every natural and thus holy urge of the oppressed person for a free debate with the unknown, for my part, metaphysical forces. This laughable rationalism, which in Russia has just discovered Darwin, exerts its influence even on the Yiddish Theater—which otherwise does not confront the laughable by-products of the Russian Revolution completely without critique. On the contrary: the Yiddish Theater in Moscow is the only place where the Jewish irony triumphs with a healthy joke over the censored and even prescribed “revolutionary” pathos. That critical talent, which is so urgently needed in the state educational institutions of the Soviets and would be sought in vain, prevails in the Yiddish theater. But an irony, which is still effective against the Narkompros2, can, applied against the Talmud, be only laughably ineffective. A trace of the futile aspiration of the Soviets to make of the Jews a “national minority” without religion, like, for instance, the Kalmyks, is still felt even in the Yiddish Theater. Not as if it were practically its spirit! But it seems to have influenced the conviction of the actors—as it must. Because one need not suddenly be a staunch anti-Semite to know that the Jews give the world its saints and its blasphemers. Some among them incline to death on the cross, others to the shattering of the cross. It would be ludicrous to speak of the influence of a Jewish knack for blasphemy on modern Russian rationalism. But one may assume that it suits many intellectual Russian Jews.

This is the child’s disease of the Yiddish Theater, like that of the Russian Revolution, like every revolution at all. The theater remains Jewish even when it attacks Jewish tradition. Because to attack the tradition is an old Jewish tradition. I was shocked even when they jeered. They caricature—but they caricature in a Jewish way. They are authentic, as authentic as the children of Israel were when Moses shattered the Ten Commandments.

Also see in:

German, Turkish, Chinese, Spanish

Zachary Suri is a rising sophomore at Yale University studying History. He is a reporter for the Yale Daily News covering Connecticut and New Haven politics, a published poet, and podcaster. Zachary also serves as Gabbai for the traditional egalitarian minyan at Yale Hillel and associate editor of Shibboleth, Yale’s Jewish studies journal.

A district of Vienna with a large Jewish population

Soviet education agency