The U.S. Army and 250 Years of American Democracy

The U.S. Army’s legacy through the personal stories of soldiers who shaped America’s democracy.

By Benjamin Griffin

This piece is adapted from a speech given by the author at the Presidio of Monterey’s 250th Army Birthday celebration on June 14th.

The United States Army celebrated the 250th anniversary of its founding on June 14th. This means that for a quarter of a millennium, it has stood ready to defend the Nation and, in doing so, became a transformative force that played an outsized role in shaping the world we live in today. I am deeply proud to have worn the uniform of the US Army since I was 17 years old. I am grateful not only for the opportunity to serve my country but also for the incredible experiences I had and the people I’ve met thanks to my time in uniform.

I am currently the commander of the 229th MI BN at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, CA, where we train soldiers to be linguists and support a myriad of missions over their careers. One of the things I love most about this command is that I play a small part in the beginning of thousands of young soldiers’ Army stories. These young men and women are at the start of something special, and I’m excited for what the future has in store for them.

It is easy to list the wars, campaigns, and battles that define the history of the Army and the nation. Saratoga, Yorktown, New Orleans, Buena Vista, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, the Meuse-Argonne, Normandy, Okinawa, Incheon, Ia Drang, 73 Easting, Mogadishu, Kandahar, and Baghdad all have a special resonance in American history because of the Army. Although it is tempting to view our military history as an inevitable machine fueled by mass and technology, it is really the individual soldiers and their actions that make success possible.

When I was a cadet at West Point, I was fortunate to hear a talk by Lieutenant General Hal Moore. Best known as the commander of 1-7 CAV during the battle of Ia Drang in the Vietnam War and the author of the book We Were Soldiers Once… and Young, along with Joe Galloway, he used his address to teach my fellow cadets and me that armies are reflections of national character. The Soviet Army he trained to fight was overly hierarchical, untrusting, and corrupt, mirroring the communist system of the Soviet Union. We see the legacy of this in the contemporary Russian army in Ukraine. What made the US Army different was not that we had the best tanks, helicopters, and rifles, because that has not been a constant of our history. Instead, we draw on talented men and women from across the great breadth of the nation, put them on teams, and unite them in common purpose.

The ability of American soldiers to draw on their personal experience and knowledge and blend that with their fellow soldiers in pursuit of victory is a national superpower. I am going to highlight just some of those soldier stories to showcase the incredible, diverse talent that authored our legacy and the type of person who still fills our ranks today.

I am going to cheat by beginning with a story from just before June 14, 1775, but it is important to recognize the citizen-soldier tradition that underlines our history. On April 19th, 1775, 80-year-old Samuel Whittemore was working his fields near Boston, Massachusetts, when he spotted reinforcements moving to assist the British forces under attack as they returned from Lexington and Concord. Alone but undaunted, Whittemore fired on the column. He killed one redcoat with his musket before using dueling pistols to fell another pair. The British soldiers surrounded Whittemore, shooting him, bayoneting him, and leaving him bleeding in his own fields to die. American militiamen discovered him soon after, not only shockingly still alive but trying to reload his musket. He died 18 years later of natural causes, seeing the American victory in the war, the adoption of the Constitution, and the first administration of George Washington. The toughness and resilience of Whittemore and those like him provided a base from which to grow an Army.

While the nascent American Army struggled initially with establishing good order and discipline, over the course of the war, it became an effective professional force, something the British often failed to recognize. Lieutenant Colonel John Eager Howard, a Marylander, used this to ruthless advantage during the Battle of the Cowpens on January 17, 1781. Recognizing that the British forces would try to exploit a fleeing militia, Howard ordered a feigned retreat, only to have the Virginia militia abruptly halt and then volley at extreme close range into the charging British units. Howard then led a bayonet charge with regulars of the 2nd Maryland Regiment, leading to the collapse of the British line and changing the trajectory of the Revolutionary War. After the American victory in the war, Howard would enter politics, rising to be the Governor of Maryland and then a U.S. Senator. After ending his political career, he became a philanthropist and was an early member of the American Antiquarian Society, which sought to preserve and make available the records of the foundation of the United States, its federal and state governments, and the movement west.

The Army was instrumental in this westward movement. Following the Louisiana Purchase, there was a need to explore and survey a vast new territory. The Corps of Discovery, led by Merriweather Lewis and William Clark, both veterans of the Legion of the United States, was filled with volunteers from the Army. Notable among these was Sergeant John Ordway of New Hampshire. Proud to be one of 25 “picked men of the Army and Country,” Ordway was the only member of the Corps to journal every day of the expedition. His diligence gifted the nation an invaluable resource into what life was like on the expedition, the nature of the environment, and encounters with Native American societies. After settling in Missouri, Ordway became a farmer, finding success until a series of earthquakes devastated the region in 1812.

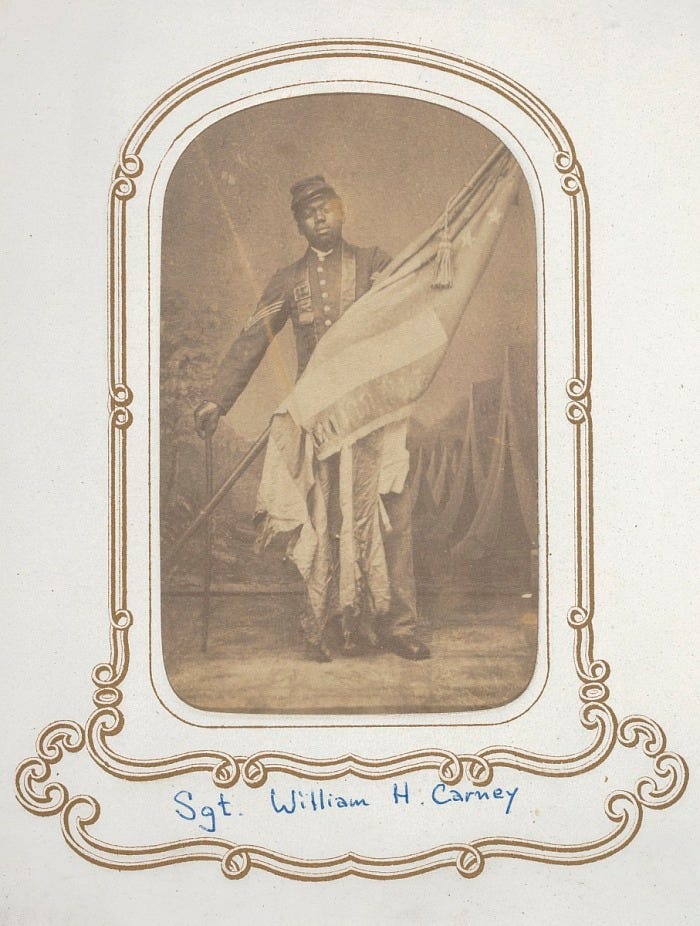

National and unit Colors are also powerful symbols, both in the Army and beyond our ranks. They represent shared national values, connections, and unit histories. It is unsurprising, then, that during the Civil War, those carrying them became targets, and soldiers who defended the colors earned the highest accolades in the war. Born into slavery in Virginia, SGT William Carney served with the 54th Massachusetts during the battle of Fort Wagner. Upon seeing the destruction of the unit's color guard, he moved forward and recovered the U.S. flag, advancing it in the assault despite his wounds. When the attack failed, and despite being wounded again multiple times, SGT Carney returned the flag to U.S. lines and, as he passed it to a fellow soldier, declared that he “only did my duty, the old flag never touched the ground.”

At the Battle of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga, Tennessee, an 18-year-old lieutenant from Wisconsin saw the regimental colors fall. Arthur MacArthur seized those colors, charging forward and planting them in the heart of rebel defenses, rallying his unit and carrying the day. Both Carney and MacArthur earned the Medal of Honor for their actions. Carney would be discharged due to his wounds and retire to Massachusetts, working as a mailman in Bedford for over three decades. MacArthur received a promotion to Colonel and eventually rose to the rank of Lieutenant General and fathered another famous general and Medal of Honor recipient, Douglas MacArthur. However, MacArthur’s role in overseeing the suppression of the Filipino insurgency after the Spanish-American War and the war crimes and torture in that campaign is a reminder of the damage done when we stray from our values. It is the Civil War actions of the “boy colonel” that still resonate today. His rallying cry of “On, Wisconsin” booms on fall Saturdays in Madison as part of the University of Wisconsin’s fight song.

While many soldiers’ heroics end up in songs, some have taken that further and composed the music themselves. Born in Alabama, James Reese Europe gained fame in New York City after conducting “The Shoo Fly Regiment,” a musical comedy about a teacher who becomes a Buffalo Soldier and serves in the Spanish-American War. Europe also felt called to serve as a soldier as the U.S. entry into the First World War loomed. Joining the Harlem Hellfighters as a Lieutenant, he commanded a machine gun company and received a ten-thousand-dollar donation to found and lead what would become the greatest military band in history. Though wounded in a gas attack, Europe recovered and went on to lead his band on a tour of France in 1918. The introduction of Jazz to an enthusiastic Paris provided the City of Lights with its soundtrack for the Roaring 20s. Shortly after returning home in 1919, a jealous bandmate murdered Europe, leading newspapers from across the country to lament the death of the “King of Jazz.”

Of course, the American Expeditionary Force provided more to France than a soundtrack. During the final German offensive of the war, the 3rd Infantry Division earned its nickname as the “Rock of the Marne.” Months later, during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, PFC John Lewis Barkley traded his sniper rifle for a newer weapon amid the heat of battle. He recovered a broken German machine gun, repaired it, and then mounted it onto a disabled French tank. From that position, he held off two German counterattacks even after taking fire from a field gun at point-blank range. PFC Barkley earned the Medal of Honor for his actions and returned home to Missouri after the war. There, he became active in the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars and was part of the site dedication for the World War I monument site in Kansas City. He also contributed to the long line of soldiers writing about war with his memoir, Scarlet Fields. Barkley’s post-war advocacy reflects how the Army forms lasting bonds between soldiers and the importance veterans place on their service for the rest of their lives.

While there are a nearly infinite number of such bonds, one particularly consequential one comes from the Italian Campaign of the Second World War. Serving in the 442nd Infantry Regiment, one of the most decorated units in the history of the Army, LT Daniel Inouye of Hawaii led his platoon against a fortified Nazi position in the Apennine Mountains, advancing despite severe wounds from being shot three times. As he readied to throw a grenade, he was shot again, severing most of his right arm and causing his hand to involuntarily clench around the projectile. Waving off aid out of concern the grenade would go off, Inouye used his left hand to pry it free and then threw it into the machine gun nest. He continued forward killing another Nazi before suffering a fifth wound. As his soldiers carried him away on a stretcher, Inouye made sure to order them back to the line to keep up the fight.

It was while he was recovering at a hospital in Michigan that Inouye met Bob Dole and started a friendship that would last the rest of their lives. LT Bob Dole, from Kansas, also fought in the Italian Campaign, though with the 10th Mountain Division. Under heavy shelling from German artillery, Dole saw Corporal Steve Sims, his platoon’s radioman, hit. Unaware that Sims’ wounds were fatal, Dole left his foxhole attempting to rescue the soldier when he too was hit, damaging his spine and leaving him with limited use of his right arm even after recovery. At Battle Creek, he and Inouye bonded over games of bridge and discussed their ambitions for the future. Dole’s plan to enter politics appealed to Inouye, as his wounds would prevent him from realizing his dream of being a doctor. By 1969, both were elected to the U.S. Senate, with Inouye never letting Dole forget that he got there first. Despite their different party affiliations, Inouye and Dole remained lifelong friends. When Inouye died in 2012, Dole, though frail, insisted on rising from his wheelchair, walking half of the Capitol Rotunda, and giving his friend a final salute as he lay in state. Dole said he “didn’t want Danny to see him in a wheelchair.”

The long careers of public service for Senators Dole and Inouye were only possible because of the medical care they received at sites where they first fell, and all the stops before they met in Michigan. One of their first treatment sites would be a field hospital such as the one Army nurse LT Cordelia “Betty” Cook of Kentucky worked at as the Allies assaulted German defenses near Presenzano, Italy. Her hospital’s position near the front lines meant it received frequent shelling. Cook remained calm in the face of enemy fire and stayed focused on caring for the wounded. Even when she was struck by shrapnel, Cook insisted on continuing to provide care for her fellow soldiers, completing her shift despite her wounds. Like Dole and Inouye, Cook opted for a life of public service after the war, working as a nurse in a Columbus, Ohio hospital for nearly thirty years.

Stories like these from the Second World War rightly fill libraries, and there is no way to do them justice in a short speech. However, before moving on, I would be remiss if I did not discuss a linguist, given that I command a unit located at the Defense Language Institute, and we trace our founding to just before the outbreak of the war due to the need for Japanese linguists.

Born in California, Kan Tagami spent parts of his youth in the United States and Japan before being drafted in February of 1941. He entered the Army as a private and completed basic training at Fort Ord. Despite the forced internment of his family after Pearl Harbor, Tagami felt a “fierce patriotism” and desire to fight for his country. He became part of the first language class conducted at Camp Savage, Minnesota, remaining at the school as an NCO instructor after graduation before volunteering to go to Burma. There, he joined the Mars Task Force and led patrols behind enemy lines, gathering intelligence and interrogating prisoners of war. Tagami’s efforts informed decisions about when to launch operations, and while on patrol, he helped his team to avoid a pursuing Japanese unit. He received a commission just as the war ended and became General Douglas MacArthur’s personal translator. Here, he assisted in the occupation of Japan and became the only member of the occupying force to have a personal audience with Emperor Hirohito. The emperor personally thanked Tagami for his role as a bridge between the two nations. Tagami retired from the Army in 1961, but he continued to work with the U.S. government as an advisor on embassy security, serving throughout Southeast Asia, including in Vietnam. Tagami shows why empathy is such an important trait in a soldier – it helps us understand our foes and care for our fellow soldiers.

The care soldiers show for one another is a constant throughout the history of the Army. Father Emil Kapaun joined the Chaplain Corps from his hometown parish in Pilsen, Kansas, serving in both the Second World War and Korean War. It was in Korea with the 8th Regiment in the 1st Cavalry Division, that Kaupan became well known for ministering at the frontline, often saying Mass using the hood of his jeep as an altar. The sudden entrance of China into the war led to his capture as he cared for the wounded and provided sacraments to the dying. Though he had an opportunity to escape after his captors were shot, Kapaun chose to remain with those too injured to move. During a 100-mile forced march, he continued to encourage his fellow soldiers and drew the ire of prison guards by preaching in captivity. After Kapaun became seriously ill, his captors intentionally neglected his care, wanting death to rid them of a troublesome priest. Yet, even as he was carried away from his fellow prisoners to the building he would die in, Kapaun forgave and blessed his captors. In February of this year, Pope Francis named Father Kapaun venerable, continuing his journey on the path to sainthood. Just a few years before, the work of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency led to the identification of his remains. Father Kapaun came home over 70 years after he fell. He is entombed in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Wichita, Kansas. Kapaun’s service demonstrated how simple acts of humanity bring light and comfort to the darkest places.

It is often small things that bring comfort to soldiers, perhaps nothing more so than a hot meal. This is what drove Chief Warrant Officer 2 Ivan Green from Illinois. A food service technician, he worked tirelessly over two tours in Vietnam to ensure soldiers of the 41st Fires Group had access to hot chow even at remote firebases deep in the jungle. He died in a helicopter crash while traveling on inspection. In 1983, Fort Sill named a dining facility after him. The facility shows the lasting bond between the Army and our Gold Star families, as over the years, Chief Green’s family has returned to serve meals to soldiers. The most recent occasion was this past Thanksgiving, when Chief Green’s daughters, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren gathered to serve over one thousand holiday meals.

I opened with a story about a citizen-soldier who picked up a musket to defend his field. That tradition still underpins our modern force, something that became even more evident during the Global War on Terror. Reserve and National Guard units deployed with breathtaking frequency to bring specialty capabilities. This is what brought SSG Timothy Nein and SGT Leigh Ann Hester of the Kentucky National Guard to Iraq. Serving in the 617th MP company, they were escorting a convoy when a group of fifty insurgents ambushed them. Their effective preparation allowed them to flank the ambush. Dismounting the vehicles, Nein and Hester cleared a trench network to relieve the pressure on the convoy. In all, eight soldiers of the 617th received awards for their valor in the Palm Sunday Ambush, including a DSC for SSG Nein and a Silver Star for SGT Hester. Both Command Sergeant Major Nein and First Sergeant Hester continue to serve in the National Guard today.

These soldiers are a tiny fragment of the tens of millions of Americans who served in the U.S. Army. It is the combination of all of them that enabled the success of the nation in ascending to its present privileged place of power. The dedication of soldiers to our oath to support and defend the Constitution, fight and win our nation’s wars, and unite through common purpose and shared values helped make the United States what it is today. This nation-making influence also stems from the fact that the service and dedication of soldiers went well beyond their time in uniform. Twenty-four presidents were either in the Active Army, Reserves, or a militia. I also highlighted three of the many members of Congress who wore our uniform.

Even more important are the advocates, mailmen, nurses, musicians, and writers. Soldiers leave the Army but continue to serve their communities, transforming their homes in part thanks to their experiences in the service. It is impossible to find a place in the United States not impacted by a soldier. Ever since George Washington assumed command of colonial militiamen outside of Boston, the U.S. Army has transformed the nation and the world. The U.S. Army defended the Constitution, and it made democracy possible. Happy Birthday, Army. This We’ll Defend.

LTC Ben Griffin is the commander of the 229th MI BN at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, CA. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Texas and is the author of Reagan’s War Stories: A Cold War Presidency. All thoughts and opinions are his own and not reflective of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, the US Army, or the Defense Language Institute.

What a great piece of history! It demonstrates the honor and pride with which so many soldiers serve. Thank you.

My Father was a Bataan Death March survivor, attended the Language School for Japanese and was stationed in Japan in 1953. This is a marvelous story of the Army and our Nation that my Dad served as a Soldier for 33 years. Thank you!