Religions Are Good For Democracy; Public Conversions By Elites Are Not

Religious diversity fuels democracy, but when faith becomes a tool for power, we risk losing the pluralism that makes democracy thrive.

Note: This will be our only column this week, but we will return to our normal schedule next week. Enjoy the New Year’s celebrations! - JS.

By Jeremi Suri

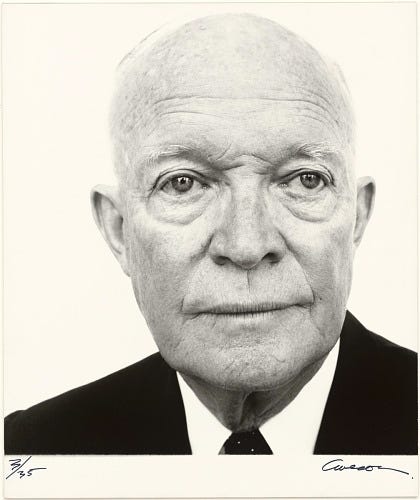

President Dwight Eisenhower, the only president baptized while in office, asserted that “our government makes no sense unless it is founded on a deeply felt religious faith.” He knew what he was talking about. He had spent his long career sending millions of young citizens into some of the deadliest battles in human history. Eisenhower frequently appealed to a higher faith for guidance, and he knew that his soldiers needed a higher faith for courage in their death-defying missions.

But Eisenhower also understood that religion in a democracy must be pluralistic, not sectarian. He closed his famous statement about the necessity of religious faith with an important caveat: “I don’t care what it is.”

The president was clear that he did not believe any particular religion should receive favor in a democracy. For him, the United States was a religious nation, not a Christian nation. Although Eisenhower had been baptized as a Presbyterian, he strenuously avoided any sectarian identification. When the pastor of the National Presbyterian Church told journalists that the president was one of his parishioners, Eisenhower instructed his press secretary: “You go and tell that goddam minister if he gives out one more story about my religious faith, I won’t join his goddam church.”

In recent months, we have seen the opposite behavior from numerous writers, activists, and politicians. Prominent conservative thinkers are announcing their conversion to Christianity. “Something profound is happening,” the Free Press trumpeted in a recent article that profiled converts, including Peter Thiel, Paul Kingsnorth, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Niall Ferguson, and even Elon Musk. Ferguson explained that these converts sought to escape what he diagnosed as a descent into nihilism and identity politics in the modern world. Religion was necessary for common meaning, he and others announced. It “provides ethical immunity to the false religions of Lenin and Hitler,” Ferguson contended. David Brooks made a similar argument in the New York Times about his own journey from Judaism to Christianity.

Conversions to Christianity or any religion are personal and often quite difficult. As a religious believer myself, I have deep respect for those who search and find a faith to guide their lives. My current concern is with the implication of so many conservatives writing in sectarian terms about their faith conversions. The new Christians in the Republican Party depict Christianity as a necessary and urgent salvation from what they define as a loss of meaning in a modern world filled with impersonal government programs, pressures for diversity, and new faiths and peoples challenging established truths. Ferguson vividly described these circumstances as “Raskolnikov’s nightmare,” referring to Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s infamous prophet of anarchist violence. Musk was perhaps even more apocalyptic: “Unless there is more bravery to stand up for what is fair and right, Christianity will perish.”

Unlike Eisenhower who treated religion (echoing Alexis de Tocqueville) as a pluralist seedbed for democratic participation, the new public Christian converts are doomsayers. We are on the edge of descent into relativism, factionalism, and a war of all against all, they argue, unless we revive core Christian values of hierarchy and nationalism. Their descriptions of faith emphasize order over chaos and traditional claims to power over new configurations. They are largely silent on the long liberationist and progressive traditions in Christianity dating back to the social gospel, civil rights, anti-colonialism, and peace activism. Their version of Christianity is dominated by male authority figures.

The Republican converts to Christianity tell us that conversion is necessary to save civilization. Those who do not convert appear ignorant or complicit in what ails society. Christianity is not just one form of democratic participation, according to this argument; it is the best route to defending essential values against an onslaught of selfish interest groups. The Free Press quotes one recent convert, Matthew Crawford: “There has to be a larger order that comprehends us and makes a demand on us.”

The “larger order” for the Republican Party of Donald Trump is a conservative interpretation of Christianity: the high church traditions of mainline protestants, popular Evangelicals, and older Catholics, not the social activism of the African-American Christian Church, the liberal Catholicism of the current Pope, or any other religious faith. The incoming Trump administration is more dominated by self-identified conservative Christians than perhaps any other since at least George W. Bush. There are few, if any, non-Christians among Trump’s cabinet nominees so far.

Flagrant public conversions to Christianity by Trump supporters make that religious choice appear as the chosen path for the Republican Party. That is exactly the presumption that Eisenhower wanted to avoid. It makes other expressions of Christianity and other faiths appear suspect, especially if they do not encourage the same values and practices. It also offers an easy excuse to dismiss the policy demands of people who do not share the same Christianity; if they are not Christians, and therefore not part of the “larger order,” how can their claims be legitimate?

Notice how immigrants are often described as non-Christian, even when they are. Notice how civil rights activists, LGBTQ+ advocates, and defenders of the poor are depicted as out of touch with religious values, when, of course, that is not true. If a traditional and hierarchical Christianity is normalized, the majority of people who see the world differently are ostracized, from the start. After all, why would you listen to people who allegedly choose anarchy and immorality over order and civilization?

This is precisely what a slide into a Christian nation looks like. The strength and vibrancy of the United States has always been its pluralism – its kaleidoscope of religious faiths. I say that as a Hindu-Jew who loves our country. What place is there for us in a country where elites tell us we should convert to Christianity to save America? What kind of democracy will exist if one religion becomes the standard identity for power? Ironically, the critics of left-leaning “woke” identity politics are creating their own Christian identity politics. “Anti-woke” for them now means Christian.

We cannot abandon religious pluralism. Diverse faiths are valuable to American democracy, and we must all speak up for the inclusion of many religions – however we interpret them – in our politics. We should treat public conversions of elite figures with respect but also caution. It is inspiring to see people find religion; it is dangerous when people use religion to join a powerful in-group, excluding many others.

Also see in:

German, Turkish, Chinese, Spanish

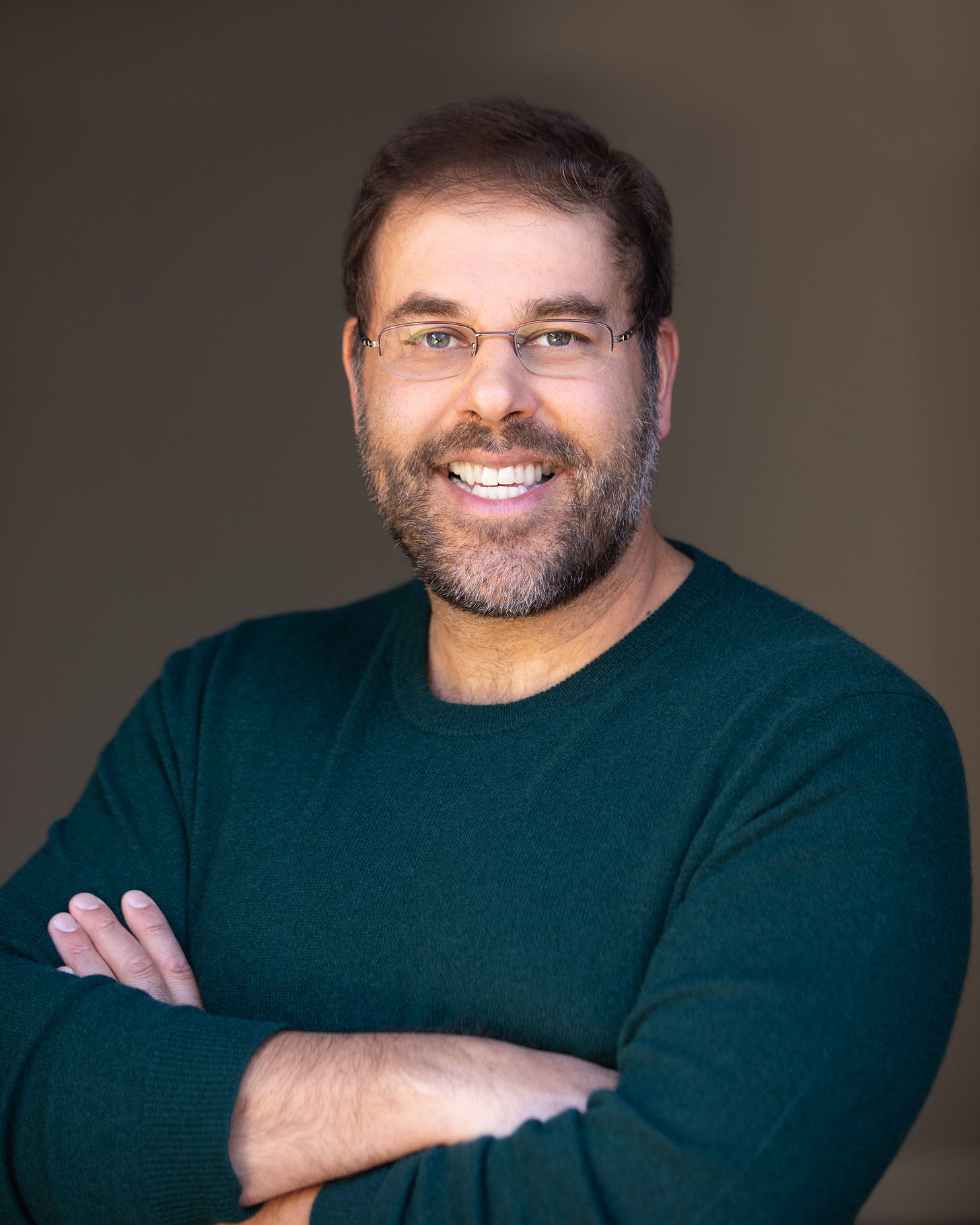

Jeremi Suri holds the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a professor in the University's Department of History and the LBJ School of Public Affairs. Professor Suri is the author and editor of eleven books on politics and foreign policy, most recently: Civil War By Other Means: America’s Long and Unfinished Fight for Democracy. His other books include: The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office; Liberty’s Surest Guardian: American Nation-Building from the Founders to Obama; Henry Kissinger and the American Century; and Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente. His writings appear in the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, CNN.com, Atlantic, Newsweek, Time, Wired, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, and other media. Professor Suri is a popular public lecturer and comments frequently on radio and television news. His writing and teaching have received numerous prizes, including the President’s Associates Teaching Excellence Award from the University of Texas and the Pro Bene Meritis Award for Contributions to the Liberal Arts. Professor Suri hosts a weekly podcast, “This is Democracy.”